Having Two Mutated Copies of the TP53 Gene As Opposed to a Single Mutated Copy Is Associated with Worse Outcomes in Myelodysplastic Syndrome and Acute Myeloid Leukemia

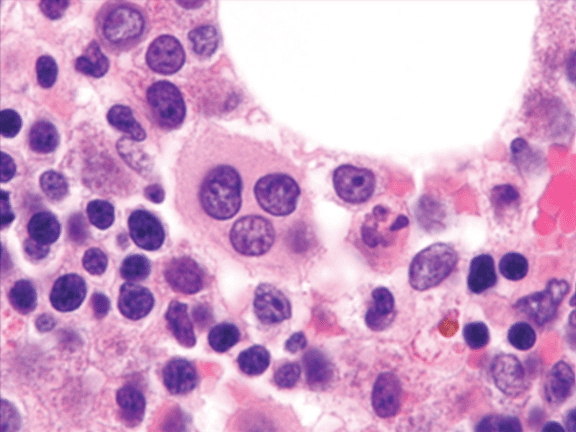

September 8, 2020: A large international study led by researchers at Memorial Sloan Kettering finds that having two mutated copies of the TP53 gene, as opposed to a single mutated copy, is associated with worse outcomes in myelodysplastic syndrome and acute myeloid leukemia. The findings have immediate clinical relevance for risk assessment and treatment of people with a blood cancer called myelodysplastic syndrome (MDS).

Considered the “guardian of the genome,” TP53 is the most commonly mutated gene in cancer. TP53’s normal function is to detect DNA damage and prevent cells from passing this damage on to daughter cells. When TP53 is mutated, the protein made from this gene (called p53) can no longer perform this protective function, which can result in cancer. Across many cancer types, mutations in TP53 are associated with much worse outcomes, like disease recurrence and shorter survival.

Considered the “guardian of the genome,” TP53 is the most commonly mutated gene in cancer. TP53’s normal function is to detect DNA damage and prevent cells from passing this damage on to daughter cells. When TP53 is mutated, the protein made from this gene (called p53) can no longer perform this protective function, which can result in cancer. Across many cancer types, mutations in TP53 are associated with much worse outcomes, like disease recurrence and shorter survival.

As with all genes, there are two copies of TP53 in our cells. One copy we get from our mothers, the other we get from our fathers. Until now, it was unclear whether a mutation in one copy of TP53 was enough to cause worse outcomes, or if mutations in both copies were necessary. A new study led by researchers at Memorial Sloan Kettering definitively answers this question for MDS, a precursor to acute myeloid leukemia.

“Our study is the first to assess the impact of having one versus two dysfunctional copies of TP53 on cancer outcomes,” says molecular geneticist Dr. Elli Papaemmanuil, a member of the Epidemiology and Biostatistics Department at MSK and the lead scientist on the study, whose results were published August 3 in the journal Nature Medicine. “From our results, it’s clear that you need to lose function of both copies to see evidence of genome instability and a high-risk clinical phenotype in MDS.”

“The consequences for cancer diagnosis and treatment are immediate and profound,” she says.

A Large, MULTICENTER Study

The study analyzed genetic and clinical data from 4,444 patients with MDS who were being treated at hospitals all over the world. Researchers from 25 centers in 12 countries were involved in the study, which was conducted under the aegis of the MDS Foundation, in collaboration with investigators from the International Working Group for Prognosis in MDS (IWG-PM) whose goal is to develop new international guidelines for the treatment of this disease. Findings were independently validated using data from the Japanese MDS working group led by Dr. Seishi Ogawa’s group at Kyoto University.

“Currently, the existing guidelines do not consider genomic data, like TP53 and other acquired mutations, when assessing a person’s prognosis or determining appropriate treatment for this disease,” says Dr. Peter Greenberg, Director of Stanford University’s MDS Center, Chair of the National Comprehensive Cancer Network Practice Guidelines Panel for MDS, and a participant in the study. “Studies are ongoing reflecting this need for change.”

This study is important in updating the IPSS-R to include molecule information in light of the more personalized treatments now being explored for MDS patients.

Using new computational methods and the database and collaborative input of the IWG-PM, the investigators found that about one-third of MDS patients had only one mutated copy of TP53. These patients had similar outcomes as patients who did not have a TP53 mutation — that is, good response to treatment, low rates of disease progression, and better survival. Two-thirds of patients, on the other hand, had two mutated copies of TP53. These patients had much worse outcomes — including treatment-resistant disease, rapid disease progression, and low overall survival. In fact, the researchers found that TP53 mutation status — either 0/1 or 2 mutated copies of the gene — was the most important variable when predicting outcomes.

“Our findings are of immediate clinical relevance to MDS patients,” Dr. Papaemmanuil says. “Going forward, all MDS patients should have their TP53 status assessed at diagnosis.”

As for why it takes two “hits” to TP53 to see an effect on cancer outcomes, Dr. Elsa Bernard, a postdoctoral scientist in the Papaemmanuil lab and the study’s first author, speculates that having one normal copy is enough to provide adequate protection against DNA damage. This would explain why having only one mutated copy was not associated with genome instability or any worse survival over having two normal copies.

Given the frequency of TP53 mutations in cancer, these results argue for examining the impact of one versus two mutations in other cancers as well. They also reveal the need for clinical trials designed specifically with these molecular differences in mind.

“With the increasing adoption of molecular profiling at the time of cancer diagnosis, we need large evidence-based studies to inform how to translate these molecular findings into optimal treatment strategies,” Dr. Papaemmanuil says.

*The MDS Foundation, Inc. is an international non-profit advocacy organization whose mission is to support and educate patients and healthcare providers with innovative research into the fields of MDS, Acute Myeloid Leukemia (AML) and related myeloid neoplasms in order to accelerate progress leading to the diagnosis, control and cure of these diseases. Visit www.mds-foundation.org to learn more.