Unforeseen costs remain a major barrier to the success of clinical trials. Studies have associated the lack of funding with the failure of clinical trials. Ideally, the process of drug development from discovery to the ready product for consumption is expected to be more than $2.5billion.1,2 This cost excludes any expenses attributed to post-approval clinical trials.

While stakeholders always consider all the associated trial costs before the process is initiated, unforeseen costs may occur after the commencement of the project. There is a need to pinpoint any source of such additional costs and nip them in the bud by allocating adequate funds to streamline the project.

Sources of unforeseen costs

Mismanagement plays a critical part in the accrual of additional expenses in clinical trials, unlike the general assumption that such costs are spontaneous. The lack of effective communication between the stakeholders in a clinical trial is a major factor driving unforeseen costs. Unrealistic expectations and poorly defined scope of work may emanate from miscommunications between such stakeholders. Such inadequacies may compromise effective clinical trial processes. Other sources of unforeseen costs may include:

Lack of information on the location of study

Inadequate or lack of information on local requirements, such as legislation and healthcare systems, may present planning and risk assessment challenges.

Failure to meet enrollment targets

Achieving the enrollment target is a critical tenet to the success of any clinical trial. Thus, failure to meet such targets is a significant dent and may compel the stakeholders to embrace alternative approaches. Such approaches may involve motivating the subjects to enrol in the study and expanding the study coverage.

Adjustments in protocol and on-site staffing

Any adjustments and on-site staffing after the commencement of a clinical trial often require additional changes, including training of new staff, additional documents, site management, and additional hours billed. These issues may adversely impact the trial process and productivity, as well as costs.

Logistical challenges

Any changes in logistics and equipment after the commencement of the trial process will likely increase the trial costs, including customs and storage fees and transportation expenses.

Strategies to Avoid Unforeseen Costs

Stakeholders must embrace elaborate planning and risk management approaches before the onset of a clinical trial to avoid any unexpected costs. Proper planning ensures that the project aligns with the objectives and goals without unnecessary deviations and delays. Any anticipated costs should be clearly stated upfront and included during the planning process.

Stakeholders should be well-versed with the local requirements of the study location to avoid both legal and financial consequences. CRO will have ample time and knowledge to craft a comprehensive mitigation plan for the project.

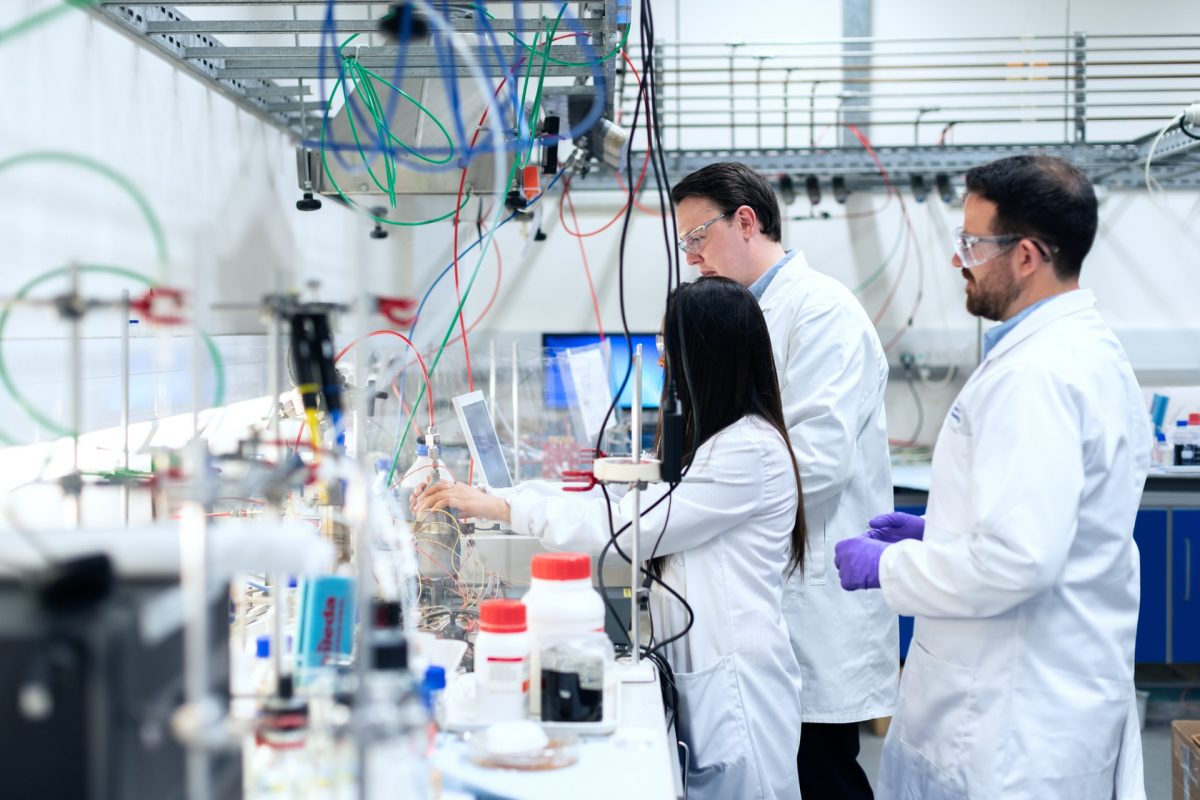

How Dokumeds helps you avoid unforeseen costs

With over 25years of experience as a CRO, Dokumeds helps organizations and sponsors conduct effective feasibility assessments. The clinical trial feasibility is instrumental in selecting and evaluating a trial site, investigators, and the recruitment process. As an experienced feasibility CRO, we understand the sponsor’s needs and gather qualitative information for an effective clinical trial process. We liaise with the local vendors and opinion leaders and identify regulatory requirements to facilitate the trial process.

References:

- DiMasi, J. A., Grabowski, H. G., & Hansen, R. W. (2015). The cost of drug development. New England Journal of Medicine, 372.

- Hwang, T. J., Carpenter, D., Lauffenburger, J. C., Wang, B., Franklin, J. M., & Kesselheim, A. S. (2016). Failure of Investigational Drugs in Late-Stage Clinical Development and Publication of Trial Results. JAMA internal medicine, 176(12), 1826–1833. https://doi.org/10.1001/jamainternmed.2016.6008